During 2022, discussions amongst mining executives have continued to focus on emerging economies. It was in September of this year that EY Global (Ernst and Young) published an important report: “Top 10 business risks and opportunities for mining and metals in 2023.” Their experts concluded that “ESG still tops the agenda for mining and metals companies, but geopolitical uncertainty, costs and supply chains also demand leaders’ focus.”

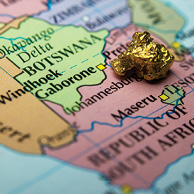

Another important research study spells out some of the harsh realities of African mining: the risks and the opportunities. “Africa’s mining potential: trends, opportunities, challenges, and strategies” was authored by Landry Signé, in collaboration with Chelsea Johnson, for the Morocco-based Policy Center for the New South.

Experts agree that there is vast untapped potential within Africa’s mining sector. But the key trends and drivers are not all helping to reduce the challenges now shaping the continent’s complex economic situation.

It is widely understood that Africa is endowed with abundant mineral resources, including gold, silver, copper, uranium, cobalt, and many other metals which are key inputs to businesses around the world. The mining sector contributes a significant share of Africa’s exports, revenue, and GDP annually. In 2019, minerals and fossil fuels accounted for over a third of exports from at least 60% of African countries. Additionally, 42 out of 54 African countries are classified as “resource dependent,” with 18 countries classified as dependent on non-fuel minerals; 10 countries classified as dependent on energy or fuel exports; and the rest being dependent on agricultural exports. Mineral resources contribute a significant amount of fiscal revenues, foreign currency reserves, and employment to a growing number of African economies, driving economic growth and development on the whole continent.

To understand the real-world dynamics awaiting Canadian mining companies active in Africa, consider the saga that is unfolding in Mozambique. The country’s mining sector is seen as a leading pathway to reducing grinding poverty in the long run. The government’s goal in welcoming miners is straightforward: to generate revenues (for both the government and the private sector), which can support infrastructure development, local economic development, and maybe even community empowerment.

Over the past decade, mining companies working in Mozambique have experienced many difficulties, most particularly since 2014 when the global commodity prices went into a tailspin. Among the many critical minerals which are mined in Mozambique, the most interesting for many miners are coal, titanium ores, precious and semi-precious stones, and gold. Coal projects suffered most. At one point, production virtually seized up due to multiple factors: the low prices, combined with the high cost of production in Mozambique; the absence of a reliable infrastructure; foreign exchange problems; and high prices for fuel.

Several non-coal mines are in various stages of development. The improved management of mineral titles, plus improved geodata, are becoming crucial to efforts which aim to move these new developments into production. The goal is to attract a new wave of exploration investment, which the national government considers to be critical to ensuring continued sector growth and replenishment of stock of available deposits.

The mining sector revitalization started but remains slow, the opening of the Nacala rail line was a big step towards revival of Tete’s coal sector. Mining in Mozambique is starting to get more attention from the national government’s key authorities, particularly because it is seen as a critical source of revenue and employment which help the economy in both the short-run to the medium-run. Mozambique has hundreds of mines, majority of which are small- and medium-scale, which require, but currently lack, supervision and oversight and proper enforcement of regulations. Mining sector employment is about 19,000 in large-scale mining sector and 120,000 in artisanal and small-scale sector (about 3% of the country’s total “formal” employment).

Artisanal mining (ASM) remains under-producing and prone to illegal activity as well is one of sources of environmental and social impacts in rural and remote areas. There is water and soil degradation, use of harmful chemicals, and use of child labor. By comparison to its neighbours (such as Tanzania or South Africa), where a lot more was done to improve ASM, including allocation of special areas and provision of various services, Mozambique is behind in its ways of handling ASM.

While illegal mining has been criminalized in the Mining Law of 2014, there is no specific training or services to address the underlying problem or to enforce this provision of the law. With poor infrastructure access and remoteness of many of the areas mined (e.g., remote border areas in the provinces of Niassa, Cabo Delgado, and Mahnica), minerals are being smuggled out of the country through neighbouring states. Mozambique’s government wants to develop more specialized services for ASM sector to improve the quality of these operations given their importance in the areas which otherwise have limited employment opportunities. With the growth of the gold and gemstone sectors, the issue of sharing the areas between large-scale and artisanal and small-scale mining will be getting only more pronounced if left unaddressed.

There are many downside risks to the mining sector in Mozambique, and political risk is at the top of that list. The lack of proper infrastructure results in a widespread inability to meet the mining sector’s basic demands. For example, Brazil’s Vale invested in the development of the Nacala corridor project for transporting coal from the mine to the seaside port of Nacala. The 912-km transport corridor has a transport capacity of 18 million tonnes of coal per year. Mozambique is heavily focused on coal, which makes the country highly susceptible to fluctuations in the price of coal. As a result of the downside risks, in 2021, Vale announced the sale of its Mozambique coal assets to Vulcan. Vale sold the company’s Moatize coal mine and the Nacala logistics corridor for a total of US$270 million.

Because of the inherent risks, in 2018, Mozambique ranked among the bottom 10 in the “Global Mining Investment Attractiveness Index,” as published by Canada’s Fraser Institute. Three years later, in 2021, the country’s position on the list had substantially improved.

According to The High Commission of Canada in Mozambique, in 2021, two-way merchandise trade between Canada and Mozambique totaled $80.5 million, comprising $39.9 million in exports from Canada and $40.6 million in imports from Mozambique.

Mozambique has commercially important deposits of coal (high-quality coking coal and thermal coal), graphite, iron ore, titanium, apatite, marble, bentonite, bauxite, kaolin, copper, gold, rubies, and tantalum.

Mozambique holds some of the world’s largest untapped coal deposits. Vale has made major investments in their coking coal mine. Their first coking coal shipments were in 2011. Opportunities for the provision of coal mining equipment and railway logistics and equipment exist. Given the expectation that mining costs in South Africa will rise considerably over the coming years, Mozambique could gain a regional competitive advantage.

Two large investment projects focused on the mining and processing of heavy sands deposits are moving forward. The Moma heavy sands project (led by Kenmare Resources, of Ireland) and Corridor sands project (owned by BHP Billiton) will require more than US$1 billion in investment. Kenmare owns and operates the Moma titanium minerals mine. Moma is one of the world’s largest titanium minerals deposits, located 160 km from the city of Nampula in Mozambique.

Mozambique’s mineral potential is largely untapped. Gold deposits in Niassa, Tete, and Manica provinces have attracted domestic and international investor interest in recent years. Increased gold mining regulation is leading to larger-scale production, as the government requires miners to formalize their legal status. Considering all of this, Xtract Resources of the U.K. acquired a gold mining concession with estimated reserves of 2.97 million oz. Gold industry production grew 1.1% annually from 2016 to 2020.

Syrah Resources of Australia made its first shipment of graphite from its Balama project in the second half of 2017 and formally inaugurated the project in April 2018. Their Balama project has a production capacity of 350,000 tonnes per annum, which represents a 40% share of the worldwide graphite market. Syrah will export most of this production to the Chinese and U.S. markets.

New Energy Minerals of Australia, formerly known as Mustang Resources, fast-tracked its Caula graphite and vanadium project in northern Mozambique. Valued at approximately US$44 million, this project is undergoing a definitive feasibility study. Total graphite deposits are estimated at 700,000 tonnes from 5.4 metric tonnes of ore, with an associated vanadium content of the ore estimated at up to 1.02%.

Baobab Resources of Australia is developing a big iron project in Tete province to supply iron and steel for regional infrastructure projects.

Gemfields of the U.K. owns a 75% stake in Montepuez Ruby Mining Limitada, which commenced operations in February 2012, and represents a $130 million investment in developing northern Mozambican ruby deposits in a concession area of 2,600 km2. Gemfields estimates that their existing concession contains an estimated 467,000 carats worth of rubies in both primary and secondary mineralization.

In 2018, Fura Gems Inc. of Canada acquired nine ruby assets in northern Mozambique from New Energy Minerals and Regius Resources Group of the U.K. As a result, Fura holds a ruby mining concession area of 1,104 km2 in northern Mozambique. Fura holds effective interests in these projects in the range of 65% to 80% with the remainder held by local partners. Fura has invested upwards of US$19 million in these projects over the following three years in a program of drilling, bulk sampling, and production mining.